Posts Categories

Latest Posts

Liberia’s Environmental Protection Agency has taken a first step to curb the air pollution that is killing and sickening Liberians. The Agency has instituted a mandate that companies operating in the country must install sensors to monitor the quality of the air around their facilities.

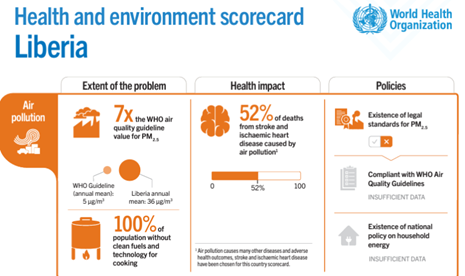

The EPA move follows a New Narratives/FPA/Spoon FM investigation earlier this year that found areas of Liberia were heavily polluted causing death and illness. Data on air quality in the country is almost non-existent – a major problem in itself according to experts– but the data that is available points to big problems. The World Health Organization’s 2023 health and environmental scored-card for Liberia found “52 percent of death from stroke and heart disease are caused by air pollution.” On average air pollution is seven times higher than WHO guidelines recommend.

Unlike Ghana and several other African countries, there are no advanced sensors to measure air quality in Liberia. But experts say there is no doubt it’s taking a toll. The number of premature deaths attributable to air pollution in Ghana each year is 28,000 according to the WHO. The comparable number given Liberia’s population would be at least 4,600. Far more are sickened.

Rafael S. Ngumbu, Manager for Environmental Research and Radiation Safety at the EPA said the new requirement will generate the needed data on air pollution, “so what that means is that at the end of the day we will now have real air quality data from each of the facilities and we can easily be able to map and track the sources of pollution.”

The companies will need to monitor the sensors through third party laboratories periodically, in some cases every quarter.

“The EPA reserves the right to periodically monitor the operations unannounced or announced,” he warned.

The EPA is also hopeful the sensors will encourage companies to self-monitor now that this regulation is in place.

This is the first major step by the EPA to address air pollution which is becoming a growing problem across the world. According to the WHO, 99 percent of the world’s population lives in places where air pollution levels exceed WHO guidelines, with air pollution causing 6.7 million deaths each year. It is especially harmful in low- and middle-income countries like Liberia, where there is none or little control on vehicle and industrial emissions and widespread use of fossil fuels such as charcoal, for cooking.

Air pollution is not just responsible for obvious illnesses like respiratory diseases like pneumonia and asthma. Tiny particles of pollution get into the bloodstream where they can cause heart disease, stroke, diabetes, blindness, infertility and cancer. Experts say, for example, that when motorbike riders die of heart attacks or stroke at unusually young ages – in their 30s and 40s – air pollution is likely a factor.

“A lot of people die from respiratory related illnesses, heart attack, high blood pressure, stroke, as a result of air pollution that comes from inhaling toxic air,” said Nathaniel Blama, former executive director of the EPA in a New Narrative/FPA interview in March this year.

The new requirement has been met by resistance by some companies said Mr. Ngumbu who is also the Liberian focal point for the Climate and Clean Air Coalition, a global body. Sensors are costly. He has urged companies to “go for low-cost sensors that are relatively low in terms of cost, but they provide some results that are reliable for readings and decision making or policy formulation.”

Companies who will refuse to comply with the new regulation risk fines from $US25,000 to $US50,000.

A graphic from the World Health Organization report shows data on Liberia’s air pollution.

Mr. Ngumbu said this is just a first step by the EPA in tackling air pollution. Vehicle emissions are a major part of the problem. There is a plan in the works to tackle vehicle emissions in the near term.

“We are working with the Climate and Clean Air Coalition, the UNFCCC and other facilities that give grants for environmental sustainability to ensure that we have a vehicle emission testing facility here, and work in line with the University of Liberia, and only vehicles that pass those tests will be allowed to ply the streets.”

A dirty cookstove in Central Accra, Ghana. Credit: Clean Air Fund/New Narratives

Waste burning and smoking and cooking over coals, wood and tires are also major problems. The WHO scorecard found 100% of the population has no access to clean fuels and technology for cooking.

Other projects including some funded by German development agency GIZ are building clean cooking capacity.

Mr. Ngumbu said that the US government is working to bring a so-called “reference grade” monitor to be installed at the US Embassy in Monrovia – similar to one installed in the US Embassy in Accra. With annual running costs as high as $US250,000 a year the Liberian government has been unwilling to foot the bill for such a monitor at this point. But the US monitor will help the EPA make the most of cheaper sensors.

“That helps us now when we have the local air quality monitors to be able to collocate it with the reference grade monitor to be able to see how our how our sensors are performing,” said Mr. Ngumbu.

For now the EPA is hoping to make the most of the rising awareness of the dangers of air pollution in the country to receive more funding for the issue in the 2025 budget.

This story is collaboration with New Narratives as part of the “Investigating Liberia” project. Funding was provided by the Swedish Embassy in Monrovia. The funder had no say in the story’s content.